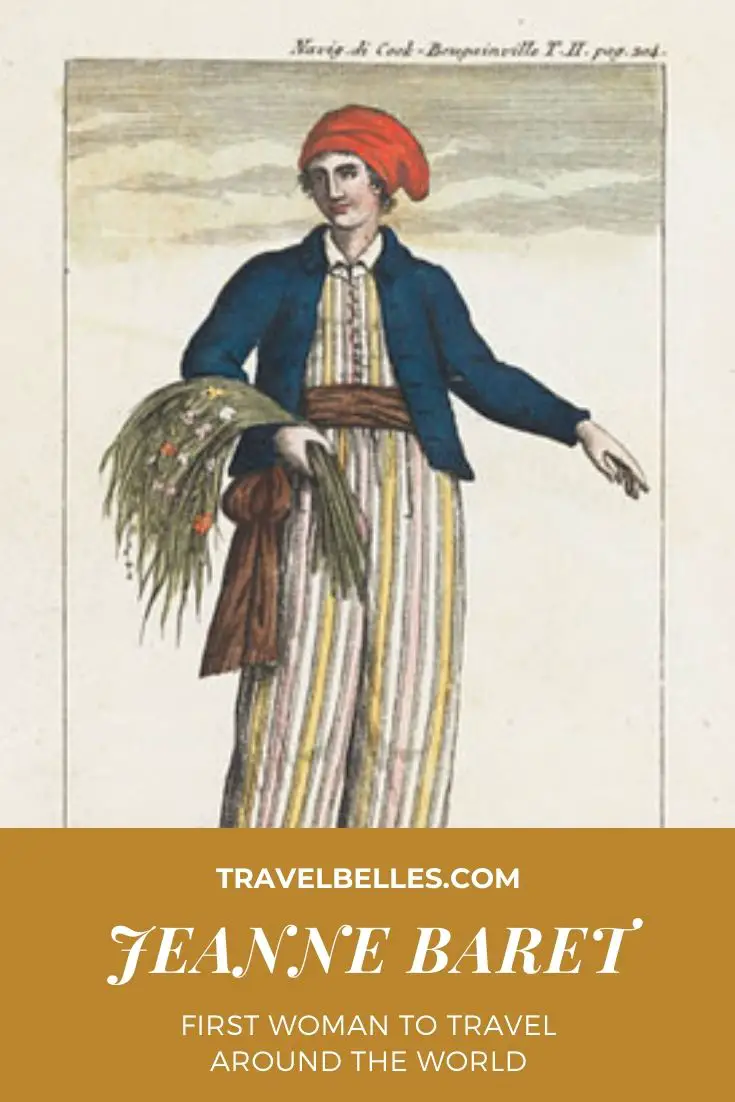

As the first woman to travel around the world, Jeanne Baret is definitely on the list as a contender for the original Travel Belle.

Neil Armstrong.

Ferdinand Magellan.

Roald Amundsen.

Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay.

The first men to set foot on the moon, circumnavigate the earth, reach the South Pole and climb Everest are well known to history.

But the first woman to travel around the world? More than 200 years later, few have heard of her.

And that’s a pity because Jeanne Baret’s story is a cracking good yarn. Her Hollywood-worthy adventures unfolded on a cramped wooden sailing ship that called at exotic destinations, such as Rio de Janeiro, the Straits of Magellan, Tahiti, New Ireland, Mauritius and Madagascar.

As the first woman to travel around the world, she made scientific discoveries, encountered indigenous people, and endured hardships ranging from starvation to assault.

All while disguised as a man.

You may also like: Iris Origo And Tales Of 20th Century Tuscany

Jeanne Baret was born to a family of poor day laborers in France’s Loire Valley in 1740. She was highly intelligent and keenly interested in the natural world. She became an “herb woman,” versed in the healing properties of local plants and sought out by residents of her village for medical treatment.

In Enlightenment Europe, herb women were also sought out by practitioners of newly-emerging sciences such as botany.

Academic knowledge of plants and animals was taught largely from textbooks at the time, so any aspiring scientist wishing to truly understand the life of plants and animals needed to consult with local people who knew them best.

One such scientist was the aristocratic Philibert de Commerson. He met Baret while studying plants in the Loire Valley. He was married but fell in love with the quick-witted country girl who knew every tree and flower.

Soon they were lovers, traveling the fields and hills collecting plant specimens. Eventually, they moved to a house in Paris, where Baret bore Commerson’s child but placed the baby in an orphanage.

Such a practice was not uncommon in 18th-century Paris, and Baret may have hoped that Commerson, whose wife had since died, might eventually marry her and agree to raise their child. Sadly, their baby died and marriage was not forthcoming.

You may also like: Meet The Travel Channel’s Samantha Brown

In 1765 the well-connected Commerson received a royal appointment to join an expedition led by the famed naval commander Louis Antoine de Bougainville.

It was to be France’s first circumnavigation of the globe. The voyage was expressly charged with collecting specimens of flora and fauna that might have commercial value and could be grown in France or its colonies around the world.

French naval regulations prohibited women aboard ships. But Commerson needed an assistant, and Baret was eager for an adventure. So she bound her breasts in tight strips of linen, donned baggy clothes, and boarded the Etoile with Commerson in Rochefort Harbor in December 1766.

From the beginning, the crew was suspicious of the scientist’s small companion, who kept to Commerson’s cabin and never seemed to use the “head,” or open-air toilet.

A group of sailors publicly confronted Baret on the deck, demanding to know her sex. Tearfully, she “confessed” to being a eunuch, a state so horrifying to the sailors that they immediately backed down.

Such a situation was not unheard of in the 18th century, as Ottoman pirates had been known to castrate their captives. It was a brilliant deception that hid Baret’s true gender while keeping her tormentors at bay.

But “eunuch” or not, Baret was subjected to the brutal hazing ritual inflicted on all new sailors during the traditional “crossing the line” ceremony when the ship passed the equator. Dragged through the water with other seamen in a sail strung beside the ship, Baret was groped and pelted with chamberpot filth.

Baret’s disguise was a misery to maintain. She had little opportunity to wash her increasingly dirt-crusted clothes. The linen straps binding her breasts chafed horribly, causing her skin to break out in hideous, constantly-weeping sores.

But when the Etoile docked in Rio de Janeiro months later, the little assistant spent days clambering though the tropical rainforest outside the city in voluminous, sweat-soaked garments. Baret gathered boxes of plant specimens for Commerson, who was laid up in his cabin with an ulcerated leg.

One plant Baret brought back was a towering woody vine with showy red flowers. Commerson named this impressive blossom “Bougainvillea” after his commander, whose ship Le Boudeuse had docked in Rio months earlier after a mission to evacuate French colonists from the Falkland Islands. This honor may have flattered Bougainville into ignoring the continuing widespread suspicions that Baret was really a woman.

The ships sailed for the Straits of Magellan. The air grew cool, then cold. Whales and seals appeared. Towering, snowcapped mountain ranges drew closer.

You may also like: What Makes You A Travel Belle?

Once the ships entered the frigid Straits, Baret and Commerson spent days clambering around rocky slopes collecting and preserving plant and animal specimens. They encountered tall, nearly-naked Fuegian aboriginal people and marveled at their ingenuity in adapting to their harsh environment.

Eventually, the ships burst out of the narrow, icy passage into the radiance of the South Pacific. They came upon numerous palm-fringed coral atolls teeming with inhabitants and dropped anchor at the largest of these islands, Tahiti.

The archipelago was unknown to them when they arrived, although the first Western explorer, the British commander Samuel Wallis, had visited the islands the previous year.

The Tahitian people welcomed the ragged French sailors enthusiastically. Bougainville named the islands “New Cythera,” and praised their inhabitants’ beauty, friendliness and apparent innocence.

Months later, Bougainville wrote in his log that a group of Tahitians had surrounded Baret and immediately realized she was a woman, to the “shock” of everyone, including Commerson! The entry read, in part:

“… she well knew when we embarked that we were going around the world and that such a voyage had raised her curiosity. She will be the first woman that ever made it, and I must do her the justice to affirm that she has always behaved on board with the most scrupulous modesty. She is neither ugly nor pretty, and is not yet twenty-five.”

Bougainville’s feigned surprise may have been due to a desire to avoid criticism for violating French naval regulations. Whatever the reason, Baret was now free of the need to maintain the fiction that she was a man. However, she once again became a target for the sailors.

When Bougainville’s ships arrived at the island of New Ireland, near New Guinea, the crew was starving. Attempts to land at islands beyond Tahiti, and on New Guinea, itself had failed due to hostile inhabitants and bad weather. Once the desperate, famished sailors finally came ashore and found food and water, they turned their attention to Baret, catching her alone on a beach.

What followed was described only vaguely in the officers’ journals, but Baret was carried back to Commerson’s cabin, where she remained for weeks in seclusion. Bougainville’s ships passed through Indonesia and on to the Indian Ocean island of Mauritius.

There, in the first French territory, they had encountered in two years, Baret and Commerson left the expedition. Why? Baret was once again pregnant, with the baby due before Bougainville’s ships could reach Europe.

It would have been impossible to hide the fact that a woman had been on board.

Baret and Commerson remained on Mauritius as guests of a hospitable governor. When the baby was born, Baret placed her second son in the foster care of a local plantation owner.

During their sojourn on Mauritius, Baret and Commerson went on an expedition to Madagascar, gathering yet more hitherto unknown species of plants and animals for the scientists in Paris.

When they returned to Mauritius, however, they found all their boxes of samples and specimens neatly packed up for departure. A new, less-accommodating governor had arrived from France.

Commeson and Baret purchased a house on Mauritius, as no landlord would rent to the peculiar couple with the stacks of smelly and strange-looking preserved plants and animals. Commerson was never to return to his native country, dying in the house from an infection.

Baret remained on Mauritius for seven years. She met and married a French naval officer who was passing through on his way home.

In the mid-1770s, the couple returned to France with the boxes of specimens, which were duly turned over to the government. Baret and her husband settled in his home in the Dordonge and disappeared from history.

However, records indicate she was awarded a comfortable pension from the French government. No one knows who secretly arranged for this reward, but suspicions fall on Bougainville.

Baret died at the ripe old age of 67, unheralded as the first woman to travel around the world. She is a spiritual ancestor of those of us who today visit every corner of the globe because “… such a voyage raised her curiosity.”

all photos in public domain

Pin for Later

What great presence of mind to call herself a eunuch. Great post. We need a film made of this inspiring story!

A movie is a great idea. Let’s hope there is more about early woman travelers to serve as an inspiration to us all.

agree, agree, agree. wonderful story and would love to see this made into a movie. What a great part it would be for a lucky actress too.

i like’t it

As a thirteen year old doing her for a research project, she’s incredibly inspiring. Thank you for this,