We clustered in the cruise ship’s bow, each one trying to be the first to spot Pitcairn Island in hazy morning sun.

A tiny bump on the horizon finally appeared.

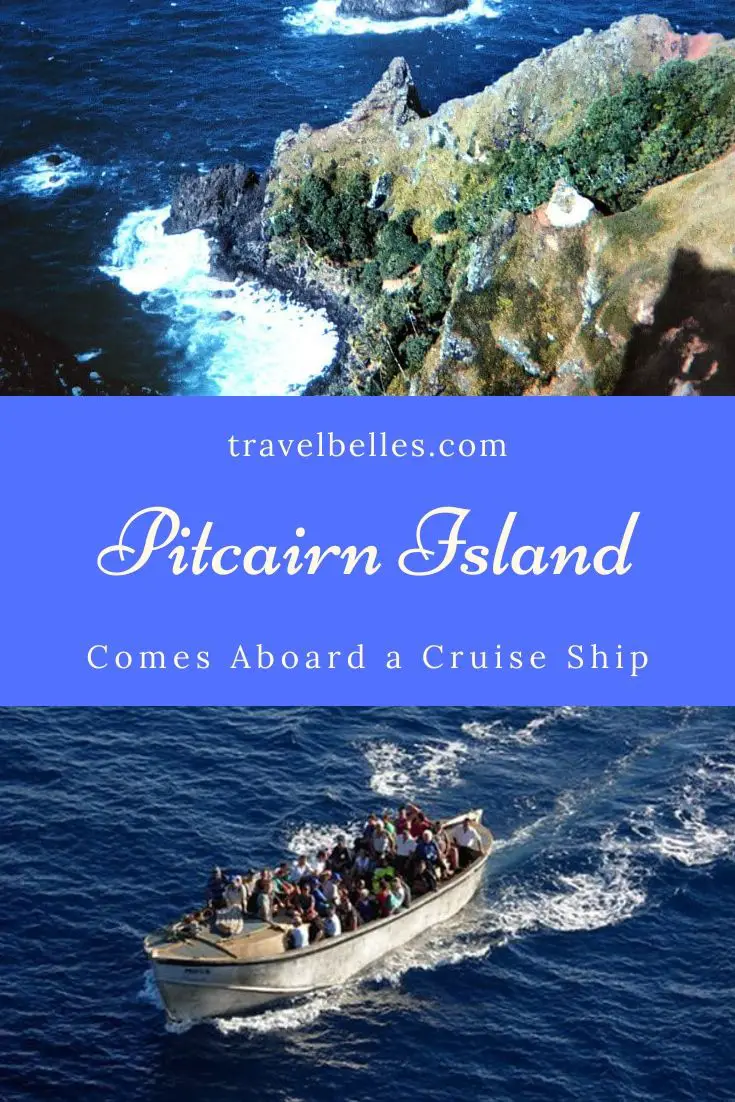

It slowly grew until we could see surf crashing against verdant hills streaked with gashes of red soil. Our ship dropped anchor off the tiny South Pacific island, home to fewer than 50 souls, almost all of whom are descendants of the mutinous Fletcher Christian, and the men and women of The Bounty, an 18th-century British Royal Navy ship.

You may also like: Tips On Avoiding The Cruise Jitters

To visit Pitcairn Island means the island, or its inhabitants, anyway, needed to come to us

With no harbor on the island and the surf much too high, it was impossible for us to land in the ship’s tender. So, the island came to us.

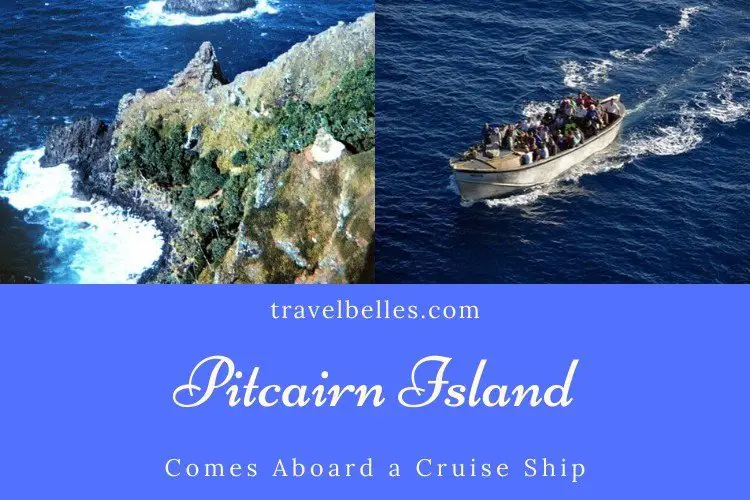

We watched as a longboat from Bounty Bay slid down a short causeway and put out to sea. Our crew dropped a rope ladder over the side while the boat headed our way. We hung over the railing watching as it was tied up to the ship and some two dozen adults, young and old, hauled bag after bundle from beneath the longboat’s decking.

They clambered up the long swinging rope ladder carrying their goods until they reached the promenade deck, eight cruise decks above the waterline.

The first item to be unpacked was a square box, each side labeled “Pitcairn Island.” It was filled with the island’s red dirt. Like the rest of the passengers, we stood in line for the photo opportunity – true tourist idiocy designed to prove we had been on Pitcairn soil.

Meanwhile, the ship’s crew set up long tables. Our visitors draped them with flags representing this tiny remnant of the defunct British Empire. Postage stamps, carvings of birds and longboats, replicas of The Bounty, postcards, local honey, T-shirts and detritus that must have washed up on their rocky shore appeared from carryalls.

You may also like: A Trip Down Under On The Queen Mary II

The signal was given and we all rushed to see the goods and what the products of generations of inbreeding looked like. Half our visitors looked like Polynesians, the men dark and the women with luxuriant long, black wavy hair. The other half looked English with fair skin and light hair.

Then there was a Chinese-looking woman, who as soon as she spotted me, whispered, “Have you got any pillow chocolates? I’m dying for a chocolate fix.”

After producing the sweets from our cabin I asked her where she was from. “Los Angeles,” she said. She and her husband were spending a few months on the island for a change of scene from their hectic lives. She popped the rapidly melting candy into her mouth between sentences.

You may also like: Best Things To Do In New Zealand

We bought a longboat model from a dark-skinned man who introduced himself as Mr. Christian and told me that he was a descendant of the original.

With his weather-beaten face he didn’t look remotely like Errol Flynn, Clark Gable, Marlon Brando or Mel Gibson, the stars who portrayed his ancestor, the instigator of the Mutiny.

He seemed a genial representative of the dwindling community, but I later learned that he had recently finished a prison sentence along with several other men convicted of rape and incest in a scandal that ripped the island populace apart for several years.

What a history: when Christian burned and sank the ship in 1790, he ensured his followers were trapped on an island measuring 1.75 square miles. The nine British crew members, 11 Polynesian women, and six kidnapped men descended into anarchy, drunkenness and murder.

It was only in 1808 when the crew of an American sealing ship managed to come ashore that the islanders were found, even though the British had been searching for them ever since the mutiny. By the time the US ship anchored, only one man, John Adams, four Tahitian women and some children remained.

Later, the population increased to more than 200 until the British government evacuated some to Norfolk Island far off the coast of Australia to avoid general starvation. Now the population is shrinking again and the island’s future is once more in doubt.

The islanders’ only income derives from selling its Internet domain suffix, .pn, postage cards, stamps and the trinkets we bought. The passengers and crew all endeavored to aid their economy, creating a frenzy of shopping as we jostled to get to the front of each table.

When the shopping was over, our visitors were invited to lunch. We sat with some of them to talk about island life: nearest airstrip 350 miles away, no way to arrive by boat when the sea was rough, Internet but restricted hours of electricity because of the difficulty in bringing in fuel for generators, a dentist and doctor who rotate in and out from New Zealand.

One woman described her lengthy shopping list for the supply ship coming from Mangareva, Tahiti every three months: large bags of flour, sugar, and other staples to supplement the fruit and vegetables grown locally. How different from my weekly list and visits to the grocery store to pick up a forgotten item.

You may also like: Eight Must-See Sydney Attractions

The sun inexorably declined in the west and it was time for us to part. Before we hugged each other in farewell, the islanders gathered to sing Polynesian songs and hymns. The last was ‘Abide with Me’:

“Abide with me; fast falls the eventide; The darkness deepens; Lord with me aide. When other helpers fail and comforts flee, Help of the helpless, O abide with me.”

I cried when I thought of their lonely lives. We were on the last of the few cruise ships that year and they had to wait for the next supply ship, months away, before seeing any outsiders again.

As we began to move away from Pitcairn Island the captain blew the ship’s horn again and again. It echoed against the cliffs and slowly faded away as the island receded off the ship’s stern.

The postcard mailed to our daughter from the island showed up on schedule – three months later.

All photos property of and by the author and used with permission.

Pin for Later

What an incredibly moving experience, to relive this story and hear the natives singing on the ocean. Amazing. 🙂

Wow! I loved this Blog entry! Almost everyone knows the Mutiny of the Bounty story, but to know that people still live on the Island over 200 years later AND they are the direct decendents. I would love to travel to Pitcairn Island. The mind is willing, the body not to much. An incredible experience and I thank the writer for sharing their experience with us. Again, thank you. I hope that Pitcairn stays full of people for years to come. And that more Cruise ships and passangers enjoy a bit of the Island.

Why does everyone close their eyes to the abuse and incest thats still ongoing?